Last time my partner and I went to Philly we visited the record store, The Long In the Truth where I was excited to find a small green book titled Sexual Physiology: A Scientific and Popular Exposition of the Fundamental Problems in Sociology by Russell Thacher Trall, published in 1874. Upon looking further into this book I have found that so many topics could be unpacked due to its connection to the work of Trall. Due to the large amount of information, I am going to have this blog consist of two parts. One will cover Trall and the Water-Cure Movement, with the second covering Sexual Physiology.

Russell Thacher Trall

Russell Thacher Trall

Russell Thacher Trall was born in Vernon, Connecticut on August 5, 1812. Trall attended Albany Medical College where he received his Medical Doctorate degree in 1835. He practiced medicine until c. 1840 when he became interested in hydrotherapy or the water-cure movement. His interest in hydrotherapy led him to dive into the movement as a physician and an authority. Four years later in New York, he established a Water-Cure institution. He then went on to found the American Hydropathic Society with Joel Shaw and Samuel R. Wells and the American Anti-Tobacco Society with Samuel R. Wells in 1849, and the New York Hydropathis and Physiological School in 1853. Both the American Hydropathic Society and the New York Hydropathis and Physiological School were later renamed to American Hygienic and Hydropathic Association of Physicians and Surgeons in 1850 and to the New York Hygeio-Therapeutic College in 1857 respectively. Ten years later in 1867, Trall moved his institutions to Florence, New Jersey where he died on September 23, 1877. (1)

Trall also wrote and edited works on hydrotherapy. He edited The Water-Cure Journal later retitled The Herald of Health. Trall also wrote the first known vegan cookbook titled The Hygeian Home Cook-Book in 1874. His other publications are Hydropathic Encyclopedia, Hand-Book of the Hygienic Medication, Uterine Diseases and Displacements, and Pathology of the Reproductive Organs. (2)

Hydrotherapy aka Water-Cure Movement

Hydrotherapy, also known as the Water-Cure Movement became popular in the United States in the 1840s. Hydrotherapy is the practice of using water for physical remedies. Using water for health benefits had existed all throughout history. A water-cure revival had occurred throughout Europe in the eighteenth century due to “the increased popularity of European spas, medical observers began writing tracts that criticized both the medicinal value of mineral water and the nonhygienic practices that abounded at Europe’s watering places. These critiques produced a spate of writing on the curative power of cold water, or hydrotherapy.” (3) The genesis of the movement in the United States stemmed from the hydrotherapy work that Vincenz Priessnitz was performing in Graefenberg, Germany. Priessnitz laid the foundation for the hydrotherapists who were to come during and after him. (4)

Historian Susan E. Cayleff described water as:

“As a cleaning agent, [water’s] universality and value are unparalleled, not only as a remover of soil but also as a metaphoric purifier of souls. The religious and mystical significance of water can be seen in its use in Christian baptism, the Jewish mikveh, and the transferring out of bad spirits from an ailing person in folk healing. Water is also the primary life-giving substance on earth. Its necessity for human, animal, and vegetative survival prompted Native American cultures to worship gods imbued with the power to deliver it. (Its power to destroy is equally undeniable: foods, tides, and drownings have taxed human understanding and control) When used topically, water is a soothing, cooling, relaxing, and stimulating agent; it is employed in a life-cycle rituals as diverse as birth, religious initiation, fertility, trials of adulthood, spiritual awakenings, sickness, death, and mourning.” (5)

Cayleff asserts that while practitioners did not describe water as possessing magical transformative powers, they also did not correct or dissuade those associations that were now being attributed to hydrotherapy. (6)

Institutions

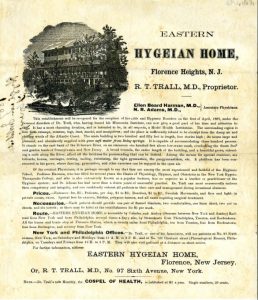

Eastern Hygeian Home, Florence Heights, N.J., R.T. Trall, proprietor (1897), Broadside, (Rutgers University)

Hydrotherapy treatment could be obtained in a variety of ways. Individuals could read manuals and administer the treatment themselves in their private homes, some practitioners did home calls, and lastly, treatment could be received by staying at an institution. How individuals obtained treatment was influenced by one’s financial position and their access to disposable time that would allow someone to stay at an institution for several days, weeks, and/or sometimes months. (7)

Many institutions sprouted up with “well over two hundred water-cure centers of healing [existing] from San Francisco to Maine… Their survival ranged from a few months to over a hundred years…”(8) Some establishments strove to be in rural areas in which their residents could have views of picture-esque sceneries that would be beneficial in their treatment. Overall the treatments at the institutions involved water “and its supporting forces of air, light food, and temperature.”(9)

Practitioners & Treatments

Those who administered hydrotherapy treatments were not required to have any kind of education but rather experience which was due to the practice being non-traditional. An attempt was made from within the movement to require practitioners to attend medical school before practicing. This push ultimately failed and “…professional criteria were largely shunned, and experience was an acceptable measure of skill.” (10) Those who administered hydrotherapy treatments did not always possess formal medical training. In addition to a variety of different educational backgrounds, there was also a push to hire women doctors at the water-cure facilities. To ensure nothing inappropriate was occurring, these businesses employed at least one woman physician for women patients who may have felt uncomfortable being treated by a man. (11 )

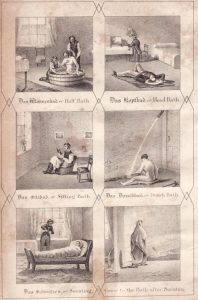

Similar to other forms of treatments, hydrotherapy was also specialized base on the symptoms or problems that the patients were experiencing. Some treatments involved being wrapped in wet sheets, or pouring cool water over one’s head in addition to other water-based acts. Hydrotherapy was not one prescription cures all, but a complex system that involved different uses of water, a restrictive diet, and fresh air. (12)

Conclusion

So much more can be written on this fascinating topic and so much already has, but for now, I am going to leave it here. Next month’s blog will focus on Russell Thacher Trall’s book Sexual Physiology: A Scientific and Popular Exposition of the Fundamental Problems in Sociology (1874). I am excited to dive into that and share information and history on the book! See you then!

So much more can be written on this fascinating topic and so much already has, but for now, I am going to leave it here. Next month’s blog will focus on Russell Thacher Trall’s book Sexual Physiology: A Scientific and Popular Exposition of the Fundamental Problems in Sociology (1874). I am excited to dive into that and share information and history on the book! See you then!

Thank you for reading!!

Sources:

(1) Susan E. Cayleff, “Ideology in Practice: Water-Cure Establishments,” Wash & Be Healed: The Water-Cure Movement and Women’s Health, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), p. 75-108; “Russell Thacher Trall,” Wikipedia.org; “Rusell Thacher Trall,” Andrew’s McNeel Publishing,

(2) “The Online Books by R.T. Trall,” Upenn Library; Russell Thacher Trall, Sexual Physiology: A Scientific and Popular Exposition of the Fundamental Problems in Sociology (1874); “Rusell Thacher Trall,” Andrew’s McNeel Publishing.

(3) Susan E. Cayleff, “Wash & Be Healed: The Hydropathic Alternative,” Wash & Be Healed: The Water-Cure Movement and Women’s Health, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), P. 19

(4) Susan E. Cayleff, “Wash & Be Healed: The Hydropathic Alternative,” Wash & Be Healed: The Water-Cure Movement and Women’s Health, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), p. 17-48; Susan E. Cayleff, “Ideology in Practice: Water-Cure Establishments,” Wash & Be Healed: The Water-Cure Movement and Women’s Health, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), p. 75-108

(5) Susan E. Cayleff, “Wash & Be Healed: The Hydropathic Alternative,” Wash & Be Healed: The Water-Cure Movement and Women’s Health, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), P. 18-19

(6) Ibid., p. 19

(7) Susan E. Cayleff, “Wash & Be Healed: The Hydropathic Alternative,” Wash & Be Healed: The Water-Cure Movement and Women’s Health, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), p. 17-48; Susan E. Cayleff, “Ideology in Practice: Water-Cure Establishments,” Wash & Be Healed: The Water-Cure Movement and Women’s Health, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), p. 75-108

(8) Susan E. Cayleff, “Ideology in Practice: Water-Cure Establishments,” Wash & Be Healed: The Water-Cure Movement and Women’s Health, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), p. 76

(9) Ibid. p. 78; Susan E. Cayleff, “Wash & Be Healed: The Hydropathic Alternative,” Wash & Be Healed: The Water-Cure Movement and Women’s Health, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), p. 25

(10) Susan E. Cayleff, “Ideology in Practice: Water-Cure Establishments,” Wash & Be Healed: The Water-Cure Movement and Women’s Health, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), p. 101

(11) Ibid., p. 91

(12) Susan E. Cayleff, “Wash & Be Healed: The Hydropathic Alternative,” Wash & Be Healed: The Water-Cure Movement and Women’s Health, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), p. 17-48; Susan E. Cayleff, “Ideology in Practice: Water-Cure Establishments,” Wash & Be Healed: The Water-Cure Movement and Women’s Health, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), p. 75-108

Leave a Reply