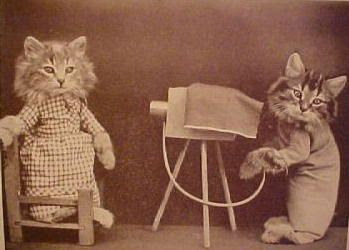

The wedding. Photo by Harry Whittier Frees, 1914.

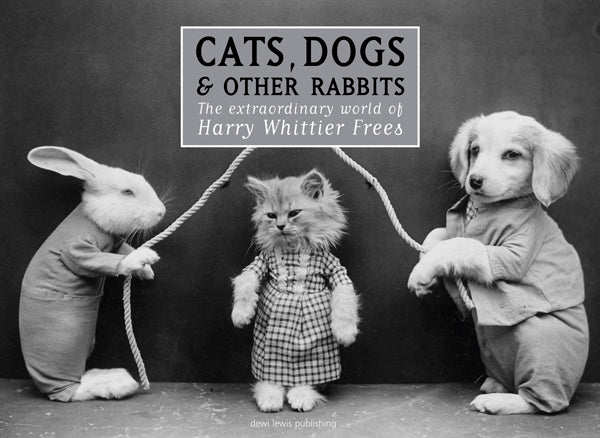

I had stumbled upon Harry Whittier Frees’ photographs almost a decade ago and instantly loved them. I was intrigued by his early 20th-century photographs of animals dressed in human attire performing various tasks, such as cooking, going on a sleigh ride, etc. While information on Frees’ is easy to find, with a simple Google search returning several results. The extent of the information is minimal, potentially due to his own privacy when he was alive or because he may not have left behind many personal papers or they were not saved or accessible. Luckily since Frees’ popularity, in addition to his father being a newspaper reporter at the time of his career, Frees’ was routinely written about in newspapers and magazines, with most scholars referring to the March 1, 1937 article on him in Life. In an attempt to learn more about Frees outside of current publications, I researched him using historic newspapers and census records. Through the construction of Frees’ career history via newspapers, his love for animals shined through the text, from the retelling of photographing instances and the formation of how his career started.

The Beginning

Harry Whittier Frees was born in Reading, Pennsylvania on June 8, 1879 to Henry Luther, a saddlemaker and later on a journalist, and Harriet Frees (nee Fry), a homemaker. Frees was the couple’s second child, with their first one being Edward L. who was born c.1877.(1) In Henry’s extensive obituary, it was printed that he followed in his father’s footsteps of becoming a saddlemaker and taking over the family harness company that he ran until his retirement in 1916. Though he took on the family business, his passion was poetry with him memorizing and writing his own and publishing three volumes of his own works, the first in 1886, the second in 1922, and the last in 1929. The first volume “concerned mainly with accounts in rythme(sic) of incidents and people of an earlier Reading.”(2) In his second volume he included a poem that was a response to the popular World War I poem, “In Flanders Field,” which was:

Sleep on, O dead; no broken faith

Shall mar your sacrifice and rest;

Already past your cross marked graves

The surgery waves of war are pressed.

Your living comrades farther on

Are bearing high the torch your bore;

You died too soon for victory’s dawn

That now illumines every shore.

In time to come look down and see

In Flanders Field your poppies bloom;

And claim it through your martyrdom.(3)

After retiring, Henry joined the Reading Eagle newspaper as a journalist in April of 1918 at 66 years old. Prior to joining the Eagle, he had worked at the Reading Herald infrequently. The opportunity at the Eagle was reportedly due to the unavailability of writers because of the US’ involvement in World War I. The position was only supposed to be to be a tryout, but he ended up working for the paper for eleven years, with him being sick the last year of his life, affecting his ability to work. On September 1, 1930 at 78 years old, Henry had died.(4)

Like his father, Frees’ also was interested in writing. He authored fiction stories in which some of them were published in newspapers. On November 10, 1903, his story “Love or Duty” was published in the Wellington, Kansas paper, The Wellington Daily News. A little less than a year later, another story of Frees, titled “Surrender”, which was printed on the Children’s page of the Guthrie, Oklahoma paper, Oklahoma Farmer, was published on June 29, 1904. A year later, on April 4, 1905 the Nashville, Tennessee newspaper, The Tennessean, shared a description of the content for a monthly magazine, The Pilgrim for April, that contained a story by Frees titled “Bradley’s Romance.” Frees ultimately changed career and became a photographer, yet writing still remained a part of his craft.(5)

The consistent history of the inspiration that led Frees into animal photography transpired at his home in 1906 when he received a doll’s hat. His cat Patches happened to be laying near the opening of the package, with the small bonnet and the cat in eyeshot, Frees was inspired to put the hat on Patches who was noted for not caring for his new accessory, but the view was comical to Frees. In one of the reporting it is printed that Frees did “not claim that he saw a whole new career opening before him in a flash, but he did want a picture of the cat all dolled up like a style revue, and he did have a glimpse of other possibilities along the same line.”(6) Although he did not see the emergence of a new chapter for himself, one did start with this moment.(7)

In the 1910 and 1920, census records Frees’s occupation was “photographer” and on his military registration card from 1918 it was “Writer of Fiction.” Yet, by 1914 his animal photography career was in full swing with him having worked at the Rotograph Company for three years already. Additionally, he published several picture books that included his photographs, which merged his two careers of writer and photographer. Some of his books were published prior to and around 1918, which would explain the occupation listed on the military registration card of 1918.(8)

The Work of an Animal Photographer

Frees’ work was difficult and one that was incredibly stressful for him as the success of his photographs were dependent upon his and the animals’ patience, in addition to access to large amounts of film. Frees worked with live animals which he reportedly did not administer any kind of sedatives, mistreat or coerce the models into giving him his desired shot. Though in an early article in the newspaper, The Reading Eagle, from February 8, 1914 it was reported that Frees had said “‘You may slap a puppy and he will forgive you but a kitten never will’ he said a kitten will invariably flinch when the hand comes near after having been treated harshly.”(9) It is unclear if he did these actions himself or was simply sharing why slapping the animals was inefficient and detrimental to his work. Either way, throughout his career in interviews he stressed the importance of kind treatment to the animals, stating that an important part of ensuring a successful aspect of the photo shoot is that “you know how to handle animals so that they do not fear you or are unduly excited by your presence.”(10) Additionally, the clothing the animals wore worked to his advantage. The costumes were sewn by Mrs. Annie Edelman, his housekeeper, and sometimes his mother, Harriet. The clothing was noted to have been stiff, with the animals pinned in, which limited their mobility, but also made the process of changing their clothing more seamless. (11)

The procedure consisted of posing the animals and taking photographs at a speed of ⅕ per second. Though he claimed a sixth sense in addition to good treatment of animals also aided in the process, Frees noted that he usually had to “junk two-thirds of his negatives.” (12)Furthermore the stress of capturing these photographs was so intense that “he photographed his furry subjects only three months out of the year.”(13) While the work was stressful, some animals were more difficult to work with than others.

Throughout Frees’ career he photographed kittens, puppies, rabbits, pigs and rarely goats and chickens. He expressed and consistently asserted that the easiest animals to capture were rabbits due to their ability to hold focus once they were engaged, with the “one exception, however, and that is his ears. These are his only means of expression and he uses them to voice all his emotions.”(14) Due to how the rabbit(s) held their ears, ultimately affected the overall image. After the rabbit, kittens were the next in line as their attention could be held with a moving object. Frees did specify a difference between cat breeds – “short haired variety” versus those that are “blue blooded breed;” asserting that “a Persian kitten is more used to being petted and made a fuss over while the more common run of cats are more matter of fact creatures and willing to take a chance on most anything.”(15) Puppies following due to them inconsistently following verbal commands. To Frees though, the most difficult animals were piglets, who were described as “eccentric.”(16)

Age of the pets also played a role in how anxiety-inducing the photoshoot would be. Frees required that the animals be babies, with kittens and puppies only being between six to ten weeks old. This was due to them being easier to work with and they also worked better with one another when the images involved different types of animals to pose together.(17)

The Models

Although Frees worked with many animals throughout his career, many stood out to him, in which he shared stories of the them by their names. The way he spoke of the animals reflected a connection he had with them and the level of agency the animals had in the work themselves. The animals in particular that made an impression on Frees were three cats named Patches, Rags, and Tiddly Winks and a goat named Mike, who had stories of them shared in newspapers. The spotlighting of their stories individualized and showed the personality of the animals.

Patches was the cat that started it all. After he played his part in Frees’ origin story, the little cat modeled in many of Frees’ pictures. It appears as though some of the fame went to his head, as he was accused of being “terribly jealous of a big Persian male [cat] whose light complexion and blue eyes were adorably adapted for female flapper roles, and who wore a party gown with all the eclat of a real duchess.”(17) To assert his dominance “on one occasion Patches chased his understudy clear out of the studio and never stopped until he had him clinging to the top-most branch of a nearby tree.”(18) The chase was not enough for Patches then “sat below telling him in a choicest cat language what would happen to some long-whiskered son-of-a-gun if he ever crossed his path again.”(19)

Rags was a cat who worked with Frees in the early 1920s and was a model that Frees used a lot. Rags was described as possessing “an unusual intellect for a cat” and was known to “keep a pose for several minutes without as much as the flicker of a whisker.” But when he has reached his limit he would “give a protesting little murmur.” To get Rags back in the modeling mood, all he needed was “a short romp on the ground, together with the choice bit of meat as a reward.”(20)

Tiddly Winks was another cat that Frees worked with, that was described as:

one of the most delightful models… because of his funny habit at jumping at every moving thing he saw; from a fluttering leaf to his own shadow. He was just a ball of yellow fluff; but he could get into more kinds of mischief than you could imagine. On one occasion he was rescued just in time, after he had jumped into a bucket without first finding out that it was half full of water.

He was one of the most difficult subjects ever photographed because it seemed impossible for him to keep still. The bulb hanging in front of the camera held an irresistible fascination for him. On one occasion [Frees] dressed him up in a pinafore and bonnet and then hoping to keep him quiet while the preliminaries were being arranged he was put in a little basket.

That didn’t suit Tiddly at all. So he crawled out of the basket and started for the door. His dress kept tripping him up and his bonnet got over one ear, but he finally reached the porch where his mother, Ruffles, was sunning herself. However, it takes a wise cat to know her own child when dressed in clothes that nature never intended it to wear. Ruffles gave her son one horrified glance, took refuge under the porch, and growled menacingly when Tiddly tried to follow her. (21)

Frees’ work was dependent on how long the animals were willing to pose. The most cooperative animals did not seem to always make a mark with Frees, which was evident with Tiddly Winks.

Mike was a goat that starred in some of Frees’ photographs. Goats were not common models in Frees’ work, described as ” a character quite unique in Mr. Frees’ studio.”(22) Mike was known to have:

…possessed all the wiles of-er-His Satanic Majestry, with the coy approach of some simple little maid of the hills. When his dinner was served he invariably upset his and spilled the milk. If the lady who fed his majesty remonstrated with him and implied that he was no gentleman, he would display his prowess as a ‘butter.’ when the dish was refilled he snapped at ease but never would he start to drunk until he had a second helping. He was a kid who was forever kidding and he met an untimely fate when he protested the right of way with a speeding automobile. (23)

The stories of the animals reflect the relationships that Frees built with his models. He saw their personalities, which allowed him to truly work with them and made him able to understand their limits which played a role in his successful career.

The End of the Shoot

While Frees’ books continued to be available he seemingly stopped working or retired sometime between 1940-1941. A short story by Frees was printed in The Wilmington Morning Star newspaper from Wilmington North Carolina on February 11,1940 that went:

“Sunset Park:”

There were once four little puppies. Their names were Wags, Tags, Rags and Obadiah. They lived with their uncle Oscar and aunt Abbie. Uncle Oscar taught them to never chase kittens. One day they were [working] in the back yard. Tags, Rags and Obadiah got tired. Tags cooked a bone stew. Rags put on his best suit and played his drum. Obadiah listened to the radio and read “Puppies, Just Puppies.” But wags kept right on working. When he finished he played with a kitten. That evening uncle Oscar said that Wags had been a good puppy so he had a ride in an airplane.(24)

After the story Frees presence disappeared from the newspaper until his passing in 1953. In August of 1941, he was invited to Reading, Pennsylvania by what appeared to be a photography group that included a Matthew Romanski. Frees turned down the invitation but sent several autographed copies of one of his books. (25)

The Man Behind the Camera

Frees was born and grew up in Reading, Pennsylvania. He then moved to Oaks District in Upper Providence Township in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, and then he moved again to Florida in c.1943. Newspapers had linked him to Audubon, which is also part of Upper Providence Township, though the census records and military records do not confirm it. Audubon was named after John James Audubon who was an 19th-century ornithologist, that was known for his work with birds and animals. Both Audubon and Frees are notable for the images they created within their lifetimes.(26)

In February of 1925, Frees was noted for living in Oaks. By December of the same year, per a newspaper article, he was now living in Audubon.(27) In another article from 1928, he was still reported on living in Audubon, with it reading that “The work that has such universal appeal is earned on in a small studio adjacent to Mr. Free’s charming home at Audubon, PA., near the home of John James Audubon, the great ornithologist.”(28) Due to the several newspaper articles over the span of three years and due to the lack of information on the census records, and Audubon being in Upper Providence Township, it is safe to assert that he did live in Audubon.

John James Audubon Artwork

Frees never married and lived with his aunt on his mother’s side, Amelia Fry, in 1910. By 1920, he was living with his widowed housekeeper, Annie E. Eddleman, and her daughter Anna K. Eddleman. Annie continued living with Frees the entirety of her life, even moving with Frees when he relocated to 709 Seneca Street in Clearwater, Florida sometime around 1943, along with her sister Sarah J. Hoy and Sarah’s husband, Thomas Hoy. The couple had arrived in Clearwater from Coshocton, Ohio. Thomas died five years after the quartet made their move, on June 27, 1948 at 79 years old. Sarah died on May 24, 1953 in a nearby nursing home at age 81. At the time of Sarah’s death, Annie was still alive at roughly 83 years old, noted in Sarah’s obituary as being “survived by two sisters, Mrs. Albert Smith of Oaks, and Mrs. C. E. Eddleman of Clearwater.” Unfortunately, no record of when Annie passed away has been found, potentially she was residing at the same nursing home as Sarah where she had lived out her life, but there is no documentation at this point to prove that was the case.(29)

Sadly the man that Annie, Sarah, and Thomas lived with in Florida, the man who had become famous nationally and internationally for the happiness he spread through his photography that were used for postcards and books passed away in his home at 709 Seneca Street sometime on March 15, 1953 at 74. He had taken his life after finding out he had been diagnosed with cancer. He was found on March 19, after his neighbors had not seen him for several days, which confirms he was living alone at this point. His obituary was short and stated that:

The death of Harry Whittier Frees, 74 of 709 Seneca St., earlier this week was a suicide Justice of Peace Olin Blakely ruled today.

Deputy Sheriff Parker Jackson said he found Frees’ body in his gas-filled home after neighbors reported he was not seen around his home. He left a note, the office said.(30)

While details of his death were included, nothing was mentioned regarding his vibrant career. Though little of his personal life is known, a lot can still be compiled about his career and evidence of his passion still exists and can be found today.

Sources:

- Mary Wegley, “Introducing Harry Whittier Frees, World-Famous Animal Photographer,” in Pennsylvania Heritage (Spring, 2014), p.1

- Reading Eagle (Reading, PA), September 1, 1930, p. 3

- Ibid., p. 3

- Ibid., p. 3

- The Wellington Daily News, (Wellington, Kansas) November 10, 1903, p.2; Oklahoma Farmer, (Guthrie, Oklahoma), June 29, 1904, p. 15; The Tennessean, (Nashville, Tennessee), April 4, 1905, p. 4; Out-of-Door Life, Vol XL, No. 5, Edited J.H. Kellogg, M.D., 1905,

- Reading Eagle, (Reading, Pennsylvania), December 26, 1926, p. 6

- Magazine Section of the Milwaukee Journal, Part 7, January 13, 1924, p. 7.

- Census Records 1910 & 1920, Upper Providence Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, FamilySearch; Military Registration Card, September 12, 1919, Harry Whittier Frees, FamilySearch.

- Reading Eagle, (Reading, Pennsylvania), February 8, 1914, p. 14

- Morning Oregonian, (Portland, OR), April 4, 1915, p. 7

- Reading Eagle, (Reading, Pennsylvania), February 8, 1914, p. 14; Mary Weigley. “Introducing Harry Whittier Frees, World-Famous Animal Photographer,” in Pennsylvania Heritage, (Spring, 2014), p. 2

- Nicholas Gilmore, “The Cat Meme Photographer from a Century Ago: A Prolific Animal Photographer Pioneered lolcats at the height of the postcard popularity,” in The Saturday Evening Post, (Sept. 10, 2018), p. 3

- Mary Weigley. “Introducing Harry Whittier Frees, World-Famous Animal Photographer,” in Pennsylvania Heritage, (Spring, 2014), p. 2

- Oregonian (Portland, OR), April 4, 1915, p. 7

- Magazine Section of the Milwaukee Journal, part 7, Jan. 13, 1942, p. 49

- Magazine Section of the Milwaukee Journal, part 7, Jan. 13, 1942, p. 47, 49; The Reading Eagle, (Reading, PA), July 8, 1928, p. 14

- Reading Eagle (Reading, PA), December 26, 1926, p. 6

- Ibid., p. 6

- Ibid., p. 6

- Ibid., p. 6

- Magazine Section of the Milwaukee Journal, part 7, Jan. 13, 1942, p. 47-48

- Ibid., p. 48

- Ibid., p. 48

- Ibid., p. 48

- The Wilmington Morning Star, (Wilmington, NC), Feb. 11, 1940, p. 17

- Reading Eagle, (Reading, PA), Aug. 7, 1941, p. 8

- Census Records 1910, 1920, 1930, Upper Providence Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, FamilySearch; Military Registration Card, September 12, 1919, Harry Whittier Frees, FamilySearch.

- Reading Eagle, (Reading, PA), Feb. 25, 1925, p. 34; Reading Eagle, (Reading, PA), Dec. 1. 1925. p. 2

- Reading Eagle, (Reading, PA), July 8, 1928, p. 14

- Census Records 1910, 1920, 1930, Upper Providence Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, FamilySearch; Census Record 1945, 1950, Pinellas, Florida, FamilySearch; The Tampa Tribune (Tampa, Florida), Jun 28, 1948, p. 2; Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg, Florida), May 26, 1953, p. 18

- The Tampa Tribune, (Tampa, FL) March 20, 1953, p. 56

Leave a Reply